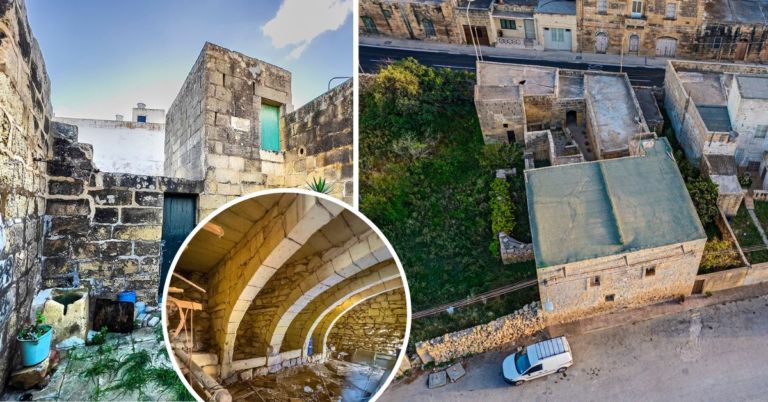

As demolition of an old house got underway this morning, a coalition of NGOs issued pictures of the interior of the centuries-old house in Xewkija that depict an interior fitting of a museum and called on the cultural authorities to intervene.

The pictures demonstrate the perverse permit granted by the Planning Authority (PA) to destroy large parts of the house and subsume the remaining skeletal walls into a large, nondescript block of 32 flats.

The coalition of Gozitan NGOs said this morning that the house is “so pristine that it could serve as a museum of typical Gozitan architecture”, and reminded the PA that it is “a government institution set up to protect and not to destroy the country.”

In answer to questions by Lovin Malta, the Superintendence of Cultural Heritage blamed the PA. “The Superintendence agrees that the building has a degree of cultural heritage value but it is the Planning Authority which issues development permits,” said Executive Officer Audrey Camilleri.

Asked whether it would intervene, Camilleri said: “The Superintendence does not have powers to reverse development permits once these has been granted.”

The development application was fronted by engineer Mark Falzon, who has a computer shop and works in software, but investigations by Lovin Malta led to Joseph Portelli and his associates as the majority owners of the property.

The PA initially refused the application, but then it granted a permit when the applicant applied a second time six days later and the case officer dropped the engulfment of the old house as a reason for refusal. This about-turn is all the more inexplicable given that the PA itself had defended its initial rejection due to the “important consideration” of averting the engulfment of the old house.

A new investigation by Lovin Malta can now reveal the series of systemic failures or omissions on the part of the Superintendence of Cultural Heritage and the PA – as well as photographs of the interior by the applicant’s architect that fail to show the true extent of the rich interior – that led to the approval of the permit.

Superintendence’s request for extensive pictures of roofing ignored

One of the roles of the Superintendence enshrined in law is “to advise and coordinate with the Planning Authority action in safeguarding cultural heritage when considering applications for planning permission relating to development affecting objects, sites, buildings or landscapes which form part of the cultural heritage.”

The Superintendence wrote five letters to the PA as the two applications for development ran their course. Analysis of these letters shows that the effort was largely one-sided, maintained by the Superintendence, which in turn weakened its own initial demands.

In the first and strongest letter, sent around seven weeks after the applicant submitted the first application, the Superintendence asked for “a detailed photographic survey of the entire property.”

It added: “Photographs should clearly show the walls and roofing techniques of the rooms, including any architectural decoration or features within the site curtilage.”

The architect, Angelo Portelli, had already submitted a set of pictures at the outset of application submissions, but these are poorly taken. Some of them are pointed from inside towards doorways, with the incoming flood of light rendering the interior dark, features obscured in the darkness. Others are underexposed, or shaky (due to camera shake). Some of the more intricate roofing does not feature in any these pictures, and neither do some of the vernacular features.

In contrast to the museum-like qualities and features, and architectural tapestry – all of which is evident in the pictures released by the NGOs – the architect’s pictures depict spaces that appear narrow, and a house that is rundown and holding few outstanding qualities.

No further submissions of additional pictures were made in response to the Superintendence’ request.

And the Superintendence did not insist on it. Instead, six weeks on, the Superintendence wrote again and this time made reference to the original set of pictures that the architect had submitted. It then commented on the oldest part of the house, writing that it is “of evident vernacular and historical value and is to be retained in its entirety, with minimal interventions.”

In taking this stance, the Superintendence implicitly accepted the demolition of the other part of the building, which according to sources also has features worthy of protection. Heritage sources expressed consternation at the rationale of implicitly accepting the demolition of part of a house, in the process destroying the house’s historical setting and evolution.

The Superintendence did not reply to one of the questions sent, on why its officials did not inspect the house as part of their assessment.

Superintendence’s advice languishes in second application

The PA then refused the permit due to the “important consideration” of averting the engulfment of the part of the house that would be subsumed by the building.

In the second application, put in 6 days after the initial refusal, the applicant proposed even heavier interventions on the part of the house that the Superintendence and the PA itself had wanted “to be retained in its entirety, with minimal interventions.” In the new architectural drawings, the roof and part of the upper wall would be lobbed off.

The Superintendence again reiterated that this part of the house had to be entirely retained, and then suggested amendments to the building by “implementing a stepped design with the height increasing further from the vernacular building.”

This was not done, yet the case officer dropped from its reasons for refusal the engulfment of the house. The Planning Commission then requested some tweaks and delivered a permit.

The commission, like the Superintendence before it, did not visit the house before granting the permit. It merely relied on the set of poor pictures – some underexposed, some shaky, the angles of view narrow, several outstanding features omitted – presented by the architect.

What do you think of the project?

Recent Comments