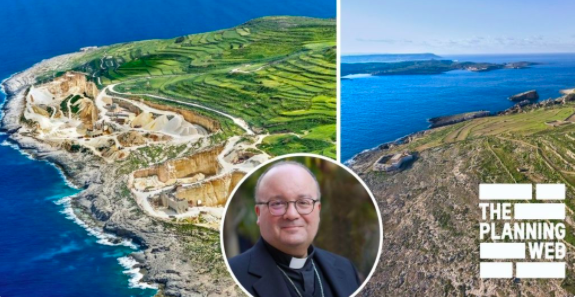

The church’s role in multi-million land deals and sprawling blocks of flats that have marred Qala’s character can be pinned to three successive Church decrees, primarily signed by Archbishop Charles Scicluna, which opened the way for the land grab of swathes of land in eastern Gozo.

The matter has caused agony to hundreds of residents and farmers and much anger directed at the church.

Lovin Malta has already reported extensively on the matter in a series of stories tagged as Gozo Grab. Now it has obtained new documents which, together with the recent testimony in court of the Archdiocese’ Property Manager Raymond Bonnici, shed new light on the land grab.

The revelations come a few weeks after Lovin Malta launched The Planning Web, a powerful new tool for heightened transparency and scrutiny of the planning system.

The vast lands originally belonged to the noblewoman Cosmana Navarra, who in 1675 put these lands in a foundation (or benefice) called the Beneficcju ta Sant Antonio delli Navarra. The point of the foundation created “for all future time” was to raise funds for pious deeds.

She created a setup in which descendants of her nephew Federico would-be patrons of the foundation, and would nominate a male, unmarried descendant as an administrator, called abbati or rector. If no male descendant could be found, then a priest could be appointed until a male descendant could take over.

Decisive power was vested in the archbishop of the time: the power to appoint (and, according to legal experts, dismiss) the rector, and the power to veto any proposed land transfer via emphyteusis by the rector.

The archdiocese’ two decrees in 2017

On 20th February 2017, Archbishop Charles Scicluna and the archdiocese’ chancellor signed two decrees. One decree appointed the lawyer Patrick Valentino as rector – despite being neither a descendant nor a priest – a decision that the archbishop took according to the testimony of archdiocese official Raymond Bonnici.

The second decree authorized the archbishop’s legal representative, Michelle Tabone, to sign a contract with Valentino (as rector) and the six Stagno Navarra siblings, who claimed to be patrons of the foundation through descent.

Bonnici admitted that the archdiocese did not ask to see evidence that the Stagno Navarras’ are descended from Cosmana or Federico.

He also said that one of the main reasons for the agreements which ceded the archbishop’s veto overland transfers was because the archdiocese was being threatened with litigation and did not want to “spend another twenty years in court.”

By contrast, the reasons given in the archbishop’s decree were mainly that the agreements were in the interest of the archdiocese and the foundation.

Archbishop Scicluna did not take up an invitation for a meeting. In response to detailed questions, the archdiocese’s highest official, Michael Pace Ross, only said that that the church “never owned the land” and only had responsibility for the “pious obligations”.

Among the elements of the contracts that are inexplicable or perplexing, there is a paragraph in the draft contract appended to the archdiocese’ decreet that specified that the lawyer Carmelo Galea and retired magistrate Dennis Montebello paid the largest individual portions of the sum of €200,000 given to the church for what Pace Ross defined as “pious obligations”.

Yet this paragraph is not found in the actual contract signed at the notary’s office seven days later by the archbishop’s legal representative, which merely says that the rector “is depositing” the €200,000 “with the archdiocese”, without saying how the rector – appointed just seven days before – got that money.

And in a second contract thirteen months later, a clause is misleading, whether wittingly or unwittingly – more on this below.

Rector signs land transfer agreements that go beyond terms of contract.

In the first contract signed by the archbishop’s legal representative Michelle Tabone, the archbishop “renounced the right” to having to give his consent to land transfers via temporary emphyteusis while retaining his veto on perpetual emphyteusis. Only perpetual emphyteusis can be converted into ownership by the lessee.

Several months later a company called Carravan Company Limited was set up, owned by the Stagno Navarra siblings, the lawyer Carmelo Galea, and a company called Carrac. The latter belongs to Dennis Montebello and his two daughters, including magistrate Rachel Montebello. Valentino, the rector, is the partner of Rachel, with whom he lives.

At around the same time, Valentino began signing preliminary agreements, otherwise known as promise of sale agreements, on foundation lands that fall within the development zone.

The first preliminary agreement promised to transfer Ta Margia – a strip of land overlooking a lush valley where dozens of residents have lived or tilled land for generations – to Dei Conti Holdings Limited, belonging to the Stagno Navarra siblings.

Early the next year two more preliminary agreements were signed with Carravan. The most valuable of these is Ta Ghar Boffa, a piece of land larger than three football pitches, on which two preliminary agreements were signed on the same day – one by Valentino to transfer land to Carravan, and the second by Carravan to sell the land to Excel Investments Limited, owned by property magnate Joseph Portelli (majority shareholder), Daniel Refalo and the Agius brothers (Ta Dirjanu).

In yet another preliminary agreement, Valentino promised to transfer Tas-Sajtun to Carravan.

These agreements were for perpetual emphyteusis. This means that Valentino was making preliminary agreements with these companies on terms that went beyond the terms agreed in the contract signed with the archdiocese. That contract expressly specified that the archbishop still had to give his consent for transfers that go beyond temporary emphyteusis.

The difference between temporary and perpetual emphyteusis is pivotal: under temporary emphyteusis, the land would return to the transferrer or owner on expiry of the lease, but property under perpetual emphyteusis can be redeemed into outright ownership.

The second contract changes temporary to perpetual

Several weeks after the preliminary agreements on Ta Ghar Boffa, the archbishop and chancellor signed another decree authorizing Michelle Tabone to “correct” the contract of 27 February 2017.

The “corrective deed” states that the parties were correcting a mistake by substituting one word with another, ‘temporary’ with ‘perpetual’.

After the correction, the relevant clause reads that the archbishop “renounces his right” to having to consent to land transfers, and then adds: “it is however being expressly agreed that the clause that prohibits the rector from making concessions or transferring foundation lands that go beyond perpetual [this was temporary in the original deed before correction] emphyteusis is not being changed.”

It is this part that is misleading because there is no such ‘clause’ – the contract of foundation does not envisage or permit any land transfers that go beyond perpetual emphyteusis in any case.

Flats march onto the pious fields

After the second contract was signed, the preliminary agreements on perpetual emphyteusis could be made good.

Two months later one of Excel’s owners, Mark Agius, applied to build 53 flats and a house at Ta Ghar Boffa. Another five applications over the following two years added yet more flats – the sprawling block, although still under construction, has already changed Qala’s townscape.

Ta Margia is now being developed by parties who made deals with Dei Conti. The daughter of Carmelo Galea is building a house there, and a proposal for a block of ten flats will be decided by Planning Authority next week.

And at Tas-Sajtun, an application for 55 flats that would dominate the skyline is currently pending at the Planning Authority.

What do you think of the land grab?

Recent Comments