The Planning Authority (PA) has dashed hopes of revoking a development permit for a block of flats, in which Joseph Portelli is the majority owner, which caused an uproar last month when workers started executing the permit and knocked down half of a centuries-old house.

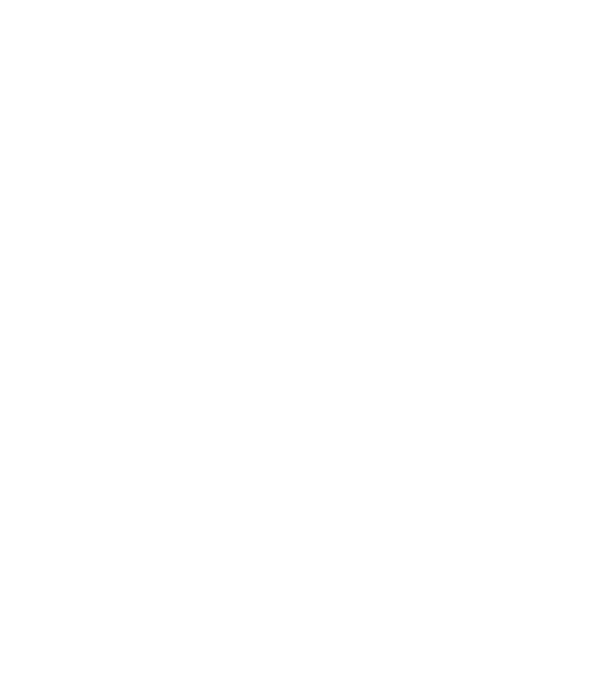

Malta’s national trust, Din L-Art Helwa, had described the house as “so pristine it could serve as a museum of typical Gozitan architecture.”

The NGO has since written to the Environment Minister to ask for an “investigation of the PA’s processes and the role of its planning officers and managers in allowing such a catastrophic event to happen to Gozo’s precious heritage.” They also separately wrote to the Environment Ombudsman to investigate the conduct of the PA, and as well as the Kamra tal-Periti (Chamber of Architects) to investigate the architect, Angelo Portelli.

The NGO said that the photographs of the interior presented by the architect “obscured or totally excluded some of the most important elements of the building which had substantial historic, social and architectural value.”

At least two features do not appear in the architect’s submission to the PA. Some pictures are also underexposed, with old arch-supporting roofs only slightly dim interior. Some other pictures are shaky.

Yet a PA spokesperson dashed hopes for revocation of the permit in answers to questions by Lovin Malta. He said that “claims made to initiate revocation proceedings in line with Article 80 of the Development Planning Act (Cap 552) are unfounded as prima facie the Interior Photo Survey and the Interior Photo Survey Plan submitted with the application portray a very detailed and thorough pictorial documentation of all the spaces within the building.”

A permit can be revoked if any information that had a “material” effect on the approval of the permit turns out to be misleading or incorrect. Proceedings for revocation can be filed by the chairperson of the Planning Authority or any other person or entity.

Lovin Malta also asked Kurt Farrugia, Superintendent of Cultural Heritage, whether the Superintendence would mount revocation proceedings itself. Farrugia said that “it is not the remit of the Superintendence to implement any actions in relation to Article 80” – revocation of the permit.

He said: “The Superintendence is aware that the photographic survey as submitted in the planning development application is not exhaustive. Whilst the photographic survey may not have been complete, the Superintendence has the necessary cultural heritage expertise to draw up the cultural heritage value of the building from the submitted information based on the characteristics of this typology of vernacular buildings.”

He added that “the Superintendence’s position was always clear and categorical: the proposed demolition and heavy alterations of this building is not acceptable from a cultural heritage point of view.”

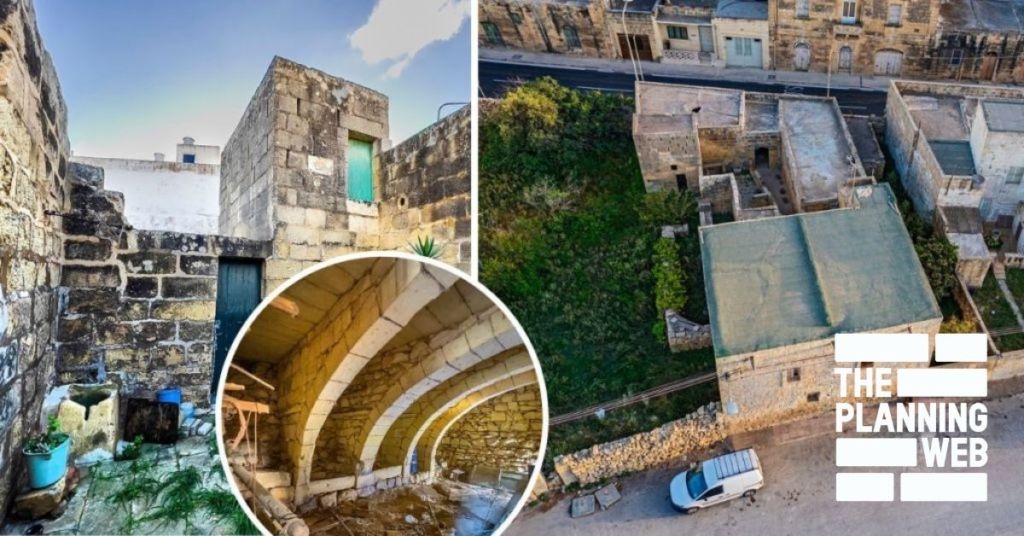

The law specifies that the PA has to consult the Superintendence, but it is not obliged to adhere to the Superintendence’s advice. In this case, the PA initially rejected a 38-flat block because it would engulf the old house. Then, after the applicant put in another application in which the number of flats was reduced to 32 flats, the PA dropped the engulfment of the old house a reason for refusal even though the interventions on the old house were heavier in the second application. A permit for the block of flats was then granted.

The development would see half the old house demolished and the other half having its roof stripped off and its skeletal remains subsumed in a nondescript block of flats. The half set for demolition – including staircases that led to the half that would remain standing – was demolished in a morning in the midst of a public uproar last month.

The application was fronted by Mark Falzon, an engineer, who declared in the application form that he was not the owner of the site but had permission from the owner to carry out the development. A Lovin Malta investigation then led to Joseph Portelli as being the majority owner of the site.

Government raised the bar on revocations

Planning sources told Lovin Malta that the PA has become increasingly averse to revoking permits, as well as acceding to requests for revocations when third parties file for revocation.

The government also made revocation proceedings more costly in a legal notice published in 2019. Prior to the legal notice, filing revocation proceedings used to be free, but the law introduced an administrative or filing fee of €500.

Sources claimed that this substantial fee introduced in subsidiary legislation (enacted by the Minister without discussion in parliament) was intended to discourage revocation proceedings. The fee is refundable to the person or entity mounting the revocation if the request is granted, yet the PA rarely accedes to revocation requests.

The government justified the fee, according to sources, by saying that it costs money for the PA to handle revocation proceedings.

But the sources lamented that, in contrast, the fee for developers to challenge enforcement actions is only €100.

Check out Lovin Malta’s Planning Web, the country’s first transparent and open platform letting you look at the ins and outs of Malta’s urban planning sector.

Victor Paul Borg has lived in various countries and worked as an author, journalist and photographer for around 25 years. His work has been published widely in many countries and is also featured on his website, victorborg.com.

What do you think of the case?

Recent Comments